In his new book, Takashi Miura, Assistant Professor in the Department of East Asian Studies, analyzes a category of Japanese divinities known as “yonaoshi gods” and their place in early modern Japan.

The expression yonaoshi is often translated as “world renewal,” and starting in the late 18th century, deified humans and supernatural entities came to be worshipped as “gods of world renewal” in Japanese society. These yonaoshi gods were invested with religious authority to rectify a variety of economic injustices in local communities, including exorbitant taxes, high prices of goods, and wealth inequality.

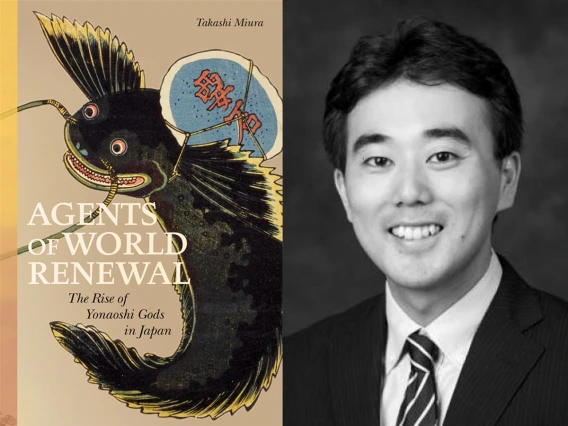

Miura’s book, Agents of World Renewal: The Rise of Yonaoshi Gods in Japan, published by the University of Hawai'i Press, offers a unique perspective in the study of Japanese religion in that it does not rely on institutional categories such as Buddhism and Shinto but rather delivers a focused analysis on the reality of religious practices “on the ground.”

“This study does not prioritize the perspective of religious institutions and seeks to shed light on localized religious practices,” Miura says. “I look at different instances in early modern Japan in which people used the concept of world renewal in pursuit of economic justice.”

Miura presents a series of discrete case studies spanning from the 1780s to 1920s, including a samurai who sacrificed his life in order to kill a corrupt ruler, disgruntled peasants who demanded that the government repeal unfair taxation, and a giant catfish believed to live beneath the Japanese archipelago and to cause earthquakes to punish the hoarding rich.

“These are not transcendental gods high above, but those who would intervene in people’s lives. This complicates our notion of what the divine is,” Miura says. “These gods are right there with you, able to address immediate economic imperatives.”

Traditionally, historians have approached the subject of yonaoshi more in line with explanations about Japan’s transformation from a feudal society to a modern nation state in the mid-nineteenth century, connecting the concept of “world renewal” to Japan’s transition, usually in Marxist terms about class struggle.

“Scholars have co-opted the world renewal deities to fit their overarching narrative of Japan moving from a closed and feudal society to one industrializing and open to the Western world,” Miura says. “Actually, the documents don’t support that. I argue that perspective alone is not enough and this book takes the concept of world renewal on its own terms.”